By Odessa Paloma Parker

Originally posted 2025-03-09 on Opaloma.ca

Sandra Meigs, Beings installation view, 2025. Photography by Toni Hafkenscheid.

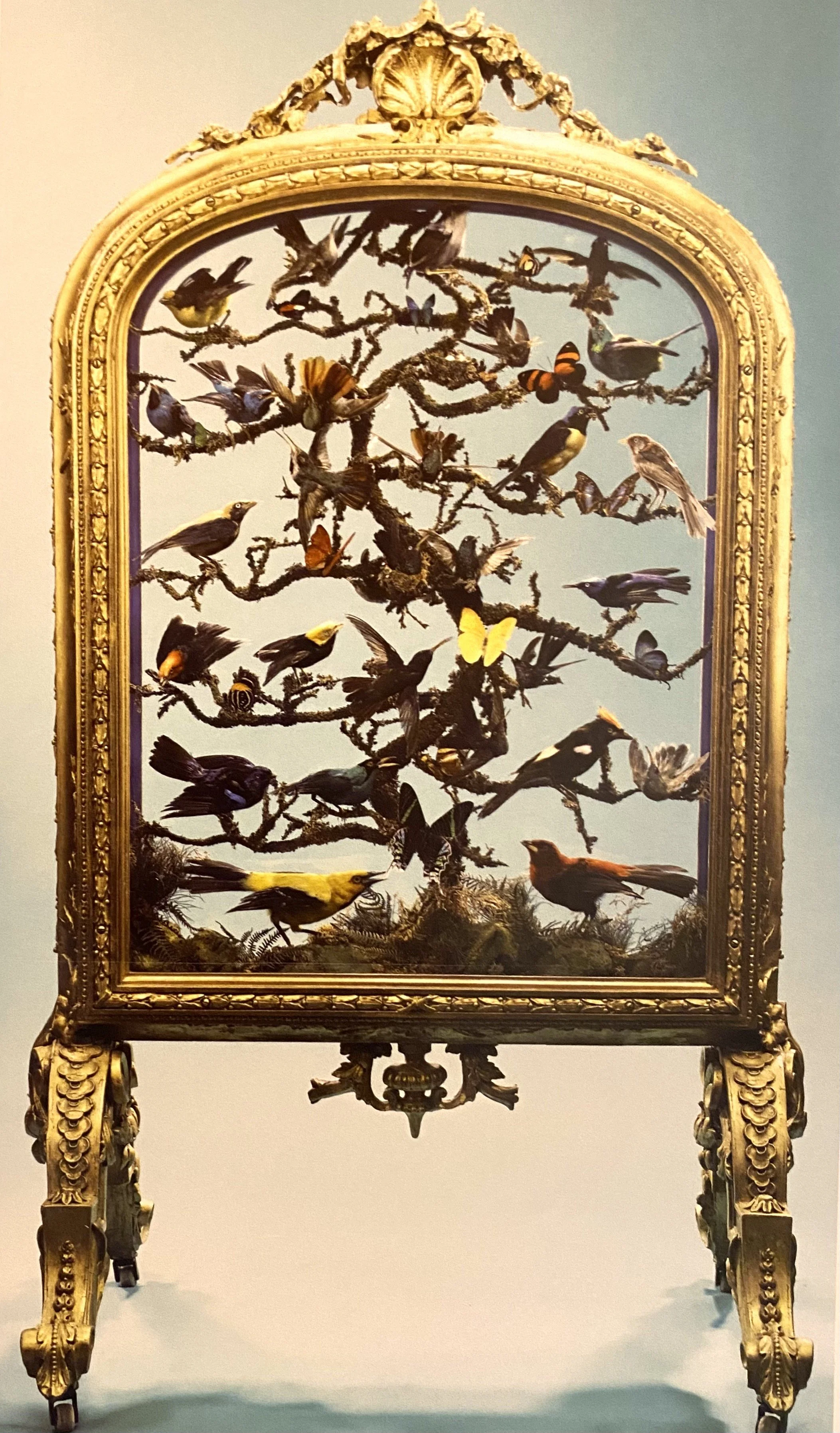

Painter Sandra Meigs articulates the relationship between humans and the environment with genuine fervour. Her show at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection in 2023, called Sublime Rage, was a monumentally vivid distillation of the effects of climate change. That same year, her show at Susan Hobbs Gallery, Bird Stuffers, examined the presence of dead birds as Victorian décor items and props in historical landscape paintings.

Between these and her other series of works, Meigs has confidently zig-zagged across styles from frenetically abstract to placidly haunting, graphic and hi-vis to subtly surreal. In the Hamilton-based artist’s current show at Susan Hobbs, Beings, she offers two collections of abstract figurative works, one 2D and the other three-dimensional. They possess a purposeful obscurity, the result of Meigs acting as a kind of artistic medium for her woodsy surroundings during a Fellowship for the Leighton Studio residency at the Banff Centre.

14 gesture-laden birch board cut outs greet you as you enter the gallery’s lower level. A few boast swirls of multiple hues that culminate in eerie facial elements; others are less chaotically colourful, but no less arresting. Upstairs in the gallery, a series of Sketches vie for attention with charismatic colour palettes and the renderings of cryptic yet emotional features.

After seeing Beings, I was curious about Meigs’s continued use of nature as muse, and here, we discuss how the show took shape.

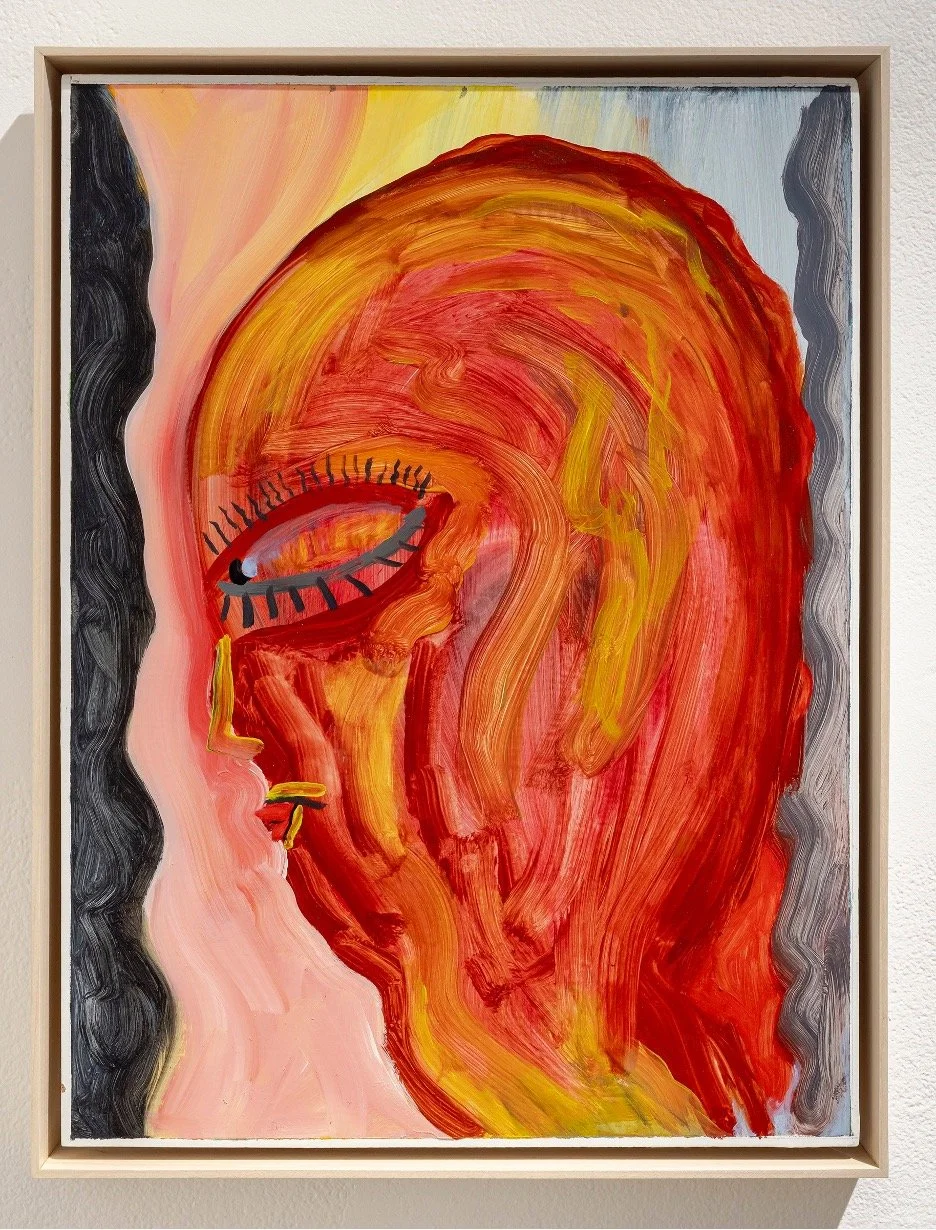

Sandra Meigs, Banff Sketch No. 2, 2023. Oil on panel (17 x 13 inches). Photography by Toni Hafkenscheid.

Tell me more about being in Banff – why were you there?

2023 was a year filled with personal difficulties for me. I was exhausted creatively and emotionally. Then, in October, serendipitously, I got an invitation to take a Fellowship for the Leighton Studio residency at the Banff Centre. The Leighton Studios are ten private cabins in the woods, each designed in the early 1980s by a Canadian architect; my cabin was by Ron Thom – a studio designed for a painter. I had it for two weeks.

At Banff, you sleep in the residence. It’s like a hotel. Then in the morning, you take a trek through the woods. There is a sign at the trailhead stating “Do not enter. Residents Only”, or something like that. There were also warning signs in the forest: Beware of Mating Elk. No kidding! Don’t get in the way of that! There was frigid snow. Streams trickling underneath the ice. Lots of wildlife around.

Then, all day, I was alone in a cabin in the woods. You forget about everything. You don’t even have to think. But rather, you’re staying immersed in meditation with your work all day long.

Dreamy! From the exhibition text, it sounds like the creation of these works was very intuitive. Can you describe the process, and how nature was guiding you?

First, about the little sketches upstairs. These came first and were made in the cabin.

Nature gave me the idea of creation and of the rawness of birth. That is how the little sketches upstairs came to be.

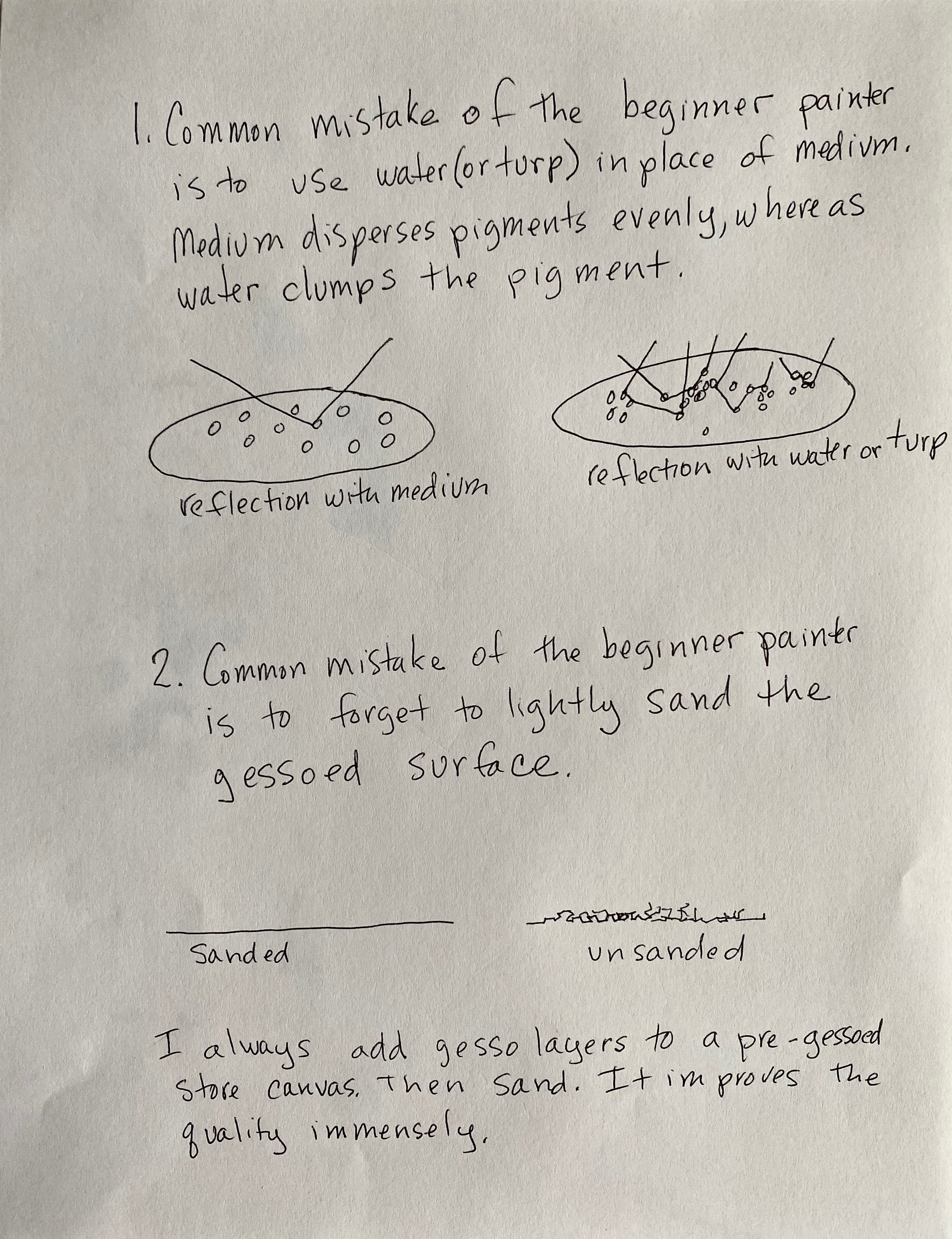

I was basically blank inside from my prior year of difficulty. Blankness is good sometimes. For painting, portraiture requires no need to research a topic either historically or theoretically – only a deep interest in the subjective self. I could simply feel free to let the painting tell me what to do. I know that sounds simple, but there I went with my gessoed panels turned vertical, ready to paint.

This back-and-forth dialogue between the painting and me felt like a kind of conception. It was like coitus with paint! [laughs] And all day! Seriously, I feel like we had a good time, the paintings and I. It was a kind of spiritual meditation, ending at dinner time and beginning again after breakfast. With some dreamtime in between.

Sandra Meigs, Banff Sketch No. 7, 2023. Oil on panel (17 x 13 inches). Photography by Toni Hafkenscheid.

The palettes in these pieces are very interesting – sometimes presenting a bit of tension. How were you selecting these colours, and why?

Oh my! I have no idea! I know that for some of them I would have a very particular notion of what colour to mix. Then, after painting the head form, it would not like it. So, I would wipe it off with a rag and start over, and in the work, you see a lot of erasing and painted over parts.

The panels are hardboard, gessoed in an oil primer, which is very slick. The oil paint is also slick, and feels very organic. Each colour of paint feels different, has a different consistency and opacity, and that feels very primal to me. I think that has something to do with why the colours look the way they do.

Some of the colours were really just an accident. Like, what is next to what leading to a new thing to be introduced. The palette was really a back-and-forth intuitive process, combined with forty years-worth of working with colour that is imbedded in me.

Let's talk about the birch cut outs. How did their shapes inform the painting choices?

I planned the forms before I thought about the colours. The forms began as a thumbnail drawing. This was then simply drawn to scale on 2-foot piece of birch panel. Then I cut it out on a table jigsaw. Much time was spent sanding and priming the form, again with the oil primer. All this hands-on time I spent with them gave me some subconscious ideas, I guess, and allowed me to get to know them naked.

As I painted, eyes often became the main feature. The eye is a holder. A great enormous container. A witness to the world. Noses for smelling out suspects. Ears for listening to truths or lies. Mouths for singing, kissing and partaking.

Sandra Meigs, Being 05.13.24, 2024. Oil on board, wood (12 ¾ x 19 ¼ x 12 ¾ inches; installed at 16 x 64 ¼ x 16 inches) (right). Photography by Toni Hafkenscheid.

This show has both two- and three-dimensional works; how do they connect?

The works upstairs, 2D, are sketches. The origin for the forms downstairs, the 3D aspect of the Beings, happened through the need to make them stand at eye level. I went through several tries with a plinth idea, or a long table idea, or a shelf on the wall idea. I think what I came up with is sort of a plinth, but it’s also a square little shelf with two legs in front. It is unadorned raw wood. So, the legs allude to a human being. The Beings had to be somewhere in the gallery, so they might as well have their own individual tabletop-with-two-legs. The wall is a vehicle for their stillness and separation.

The way the Beings are set up in the gallery is interesting. On one hand, it's like they're lined up for thoughtful inspection – like they're presenting themselves. But in another way, with them up against the wall, it's like they have a bit of physical reticence in being seen.

Oh, that’s a good way to put it. The reticence is in them being seen individually, I think. I’ve thought about this, and I did try out the idea of grouping them in a huddle on a high table. It was surely a different way to see them. More like a social group. But I think in the end they want to be alone. They give of their own individual essence much better that way. They are reticent to engage with one another, but quite happy to be quietly seen.

Sandra Meigs's Beings is on until April 5, 2025 at Susan Hobbs Gallery.